The Washington Post

Before he won Oscars for his music, composer Howard Shore helped kick off SNL

By Tim Greiving

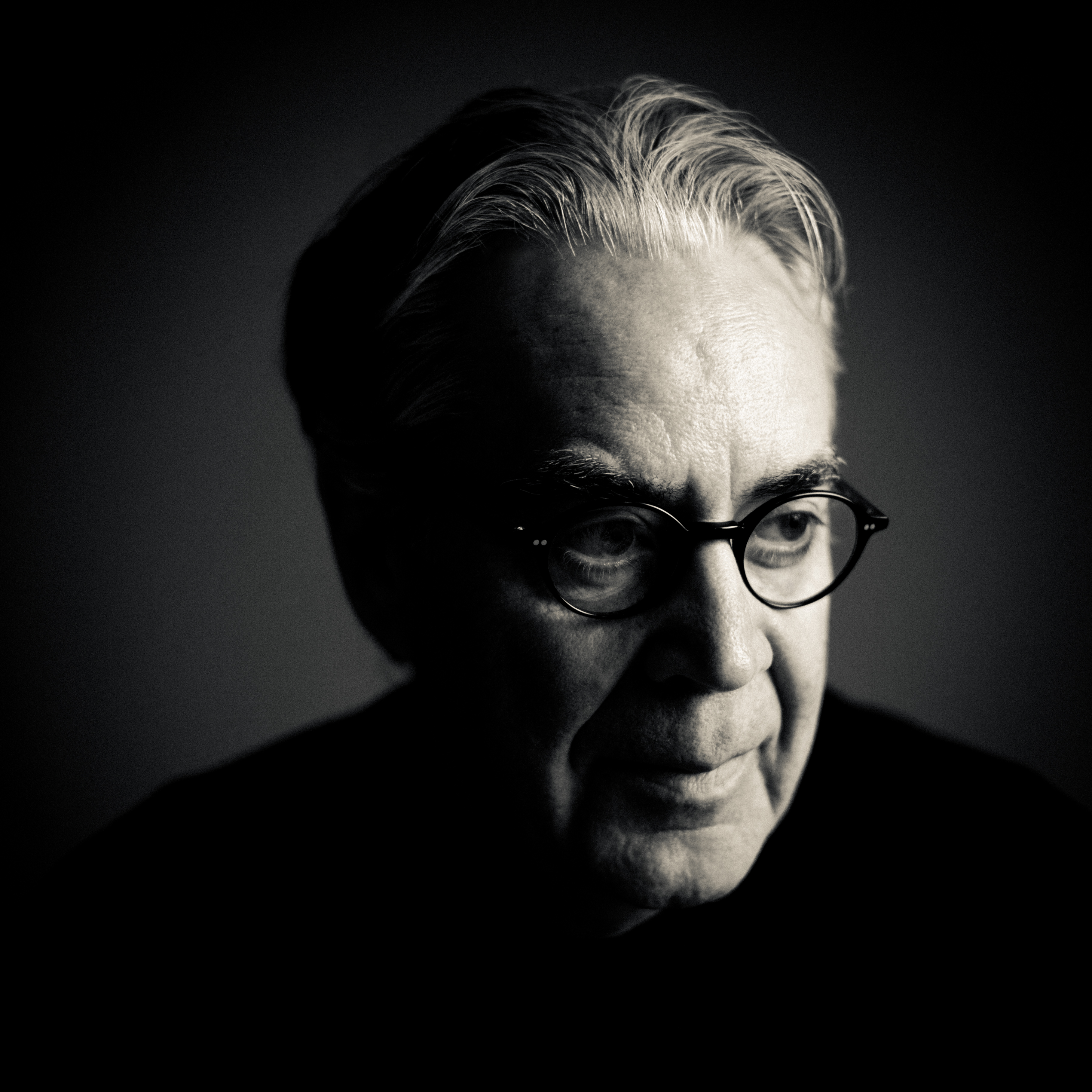

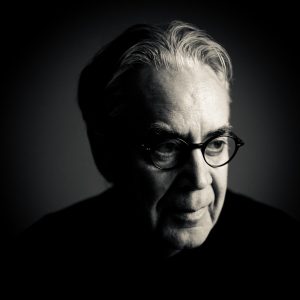

Howard Shore won three Oscars for his work on Peter Jackson’s “Lord of the Rings” trilogy. He studied music from a young age and then became musical director of “Saturday Night Live.” (Benjamin Ealovega)

Composer Howard Shore is a refined man. His music, from the Oscar-winning scores for the “Lord of the Rings” films to his recent concertos for piano and cello, favors long melodic lines and unmessy orchestration.

“There’s a clarity of music that I think reflects his clarity of thought,” suggested his old friend and bandmate Paul Hoffert.

But this same Howard Shore first introduced himself to viewing audiences as the musical director of “Saturday Night Live,” where he sang in drag with his All-Nurse Band and, as Dr. Frankenstein, reanimated Madeline Kahn’s Bride of Frankenstein to sing Stephen Sondheim’s “I Feel Pretty.”

Yet even here, and in Shore’s broader role creating the musical personality of the sketch-comedy giant, is evidence of the composer’s seriousness.

“Watching Howard take an LP out of its cover and sleeve and put it on a turntable and brush it — it wasn’t anything he did haphazardly,” SNL creator Lorne Michaels said. “I was always in more of a hurry than he was.”

Michaels and Shore grew up in the same neighborhood in Toronto and met as teenagers at summer camp, where they put on shows together, including “The Fantasticks.”

“We were pretty good,” Michaels said dryly. “Just a summer camp in Canada — but the plays were taken seriously.”

Shore’s earliest musical diet included his parents’ Elvis and Glenn Miller records, the B-movie scores he heard on afternoon television, and the songs filling the synagogue his father helped build. His aptitude was caught at the age of 8, thanks to the Canadian school system’s nationwide use of the Seashore Measures of Musical Talent tests.

He promptly began taking clarinet lessons. “I studied harmony and counterpoint, and I kept the pencil going,” said Shore, 70, employing his oft-used mantra for composition. (He still writes with pencil and paper today.) “I studied a lot of different instruments — woodwinds and piano and brass and cello. And then I finally put everything away and just kept the pencil going.”

Jazz became his main squeeze before he turned 10, and he picked up the alto sax.

“It was exciting,” he said, “and it was mysterious. I would listen to Ellington and go, ‘What is that? How do you create that kind of sound?’ The energy, the creative flow of it — I still love it to this day, because it’s not about following; it’s about equal participation.”

Michaels (then Lorne Lipowitz) remembered listening to John Coltrane records in Shore’s basement, and Shore’s father calling down to “play the melody!” Shore giggled at the anecdote and said Michaels still quotes his father’s phrase as a sign-off from phone calls.

After high school, Shore majored in composition at the Berklee College of Music in Boston. While he was in school, Michaels introduced him to Hoffert, a fellow Torontonian who was starting a jazz-flavored band and wanted Shore to join their brass section.

For the next five years Shore recorded and toured with Lighthouse, one of Canada’s most popular bands on the front lines of jazz fusion. They opened for Jimi Hendrix at the Isle of Wight; in Philadelphia, Elton John opened for them.

In addition to playing, Shore also wrote charts and occasionally sang, and when the band began playing with symphony orchestras around Canada, he got to flex his classical muscles by writing orchestral arrangements.

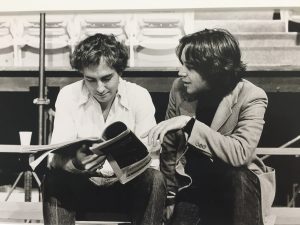

Shore, right, with “Saturday Night Live” creator Lorne Michaels in the show’s early days. (Edie Baskin)

Rise to fame

Michaels was simultaneously creating variety shows for Canadian Broadcasting Corp. radio and television (precursors to SNL), and he invited Shore to handle musical responsibilities.

“If it was anything to do with music, Howard would have been there,” said Michaels, who moved to New York in 1975 and launched “Saturday Night Live” on NBC — bringing Shore along with him.

“Unlike, say, anything else in the comedy part of it, where there would have been huge discussions,” Michaels said, “in that, I would just go, ‘Howard, are you sure you know what you’re doing here?’ and that would have been the extent of it.”

Shore was a core member of the show’s small, ragtag team and not only composed the free-form jazz pieces that opened and closed the show (and have for 42 years) but also wrote songs and dramatic underscores, appeared in sketches and was in charge of booking musical guests.

“We had Keith Jarrett, we had Sun Ra, we had Leon Redbone,” Michaels said. “We were very, I won’t go with the word ‘earnest,’ because it makes it sound a little more serious, but we were very driven for it to be good — a notion of good that seemed very clear to us.”

Shore scored his first feature film, “I Miss You, Hugs and Kisses” — a low-budget, Canadian murder movie — in 1978. He courted another Toronto filmmaker, David Cronenberg, whose early work he had seen as a teenager, asking whether he could score “The Brood,” an eerie chiller that foreshadowed their next 30-plus years of collaboration.

“It wasn’t a matter of ego for him, it wasn’t a desire to establish a signature style that would be recognizable in every film,” Cronenberg said.

With the help of library books, Shore taught himself the mechanics of scoring and synchronizing music to film. His score for “The Brood” was composed for a mere 21 strings, but it planted seeds of style and process he has continued to use — and evolve — throughout his career.

“I just try to feel something and create that,” Shore said, “because music is an emotional language, so I try to capture the feeling of it, what I’m after. It’s not that technical, and it’s not about technology. Maybe that’s why I worked in film so much, because a lot of it is about capturing the feeling of a scene.”

Cronenberg became Shore’s most frequent collaborator, and he gave the composer freedom to experiment with unconventional ideas in “Scanners” (1981) and “Videodrome” (1983) up through “The Fly” (1986) and recent fare such as “Maps to the Stars” (2015).

“Howard became kind of a character actor,” said Cronenberg, who suggested that the emotion Shore is especially gifted at evoking is “the strange and terrible sensuality of loss.” “The music would add something — add some dialogue, add a level of understanding or suggestion or provocativeness — rather than amplify what was already there.”

Shore lived off SNL royalties for almost a decade, but he gradually realized he had become a career film composer as he received offers from directors including Jonathan Demme (“The Silence of the Lambs”), Martin Scorsese (“The Departed”) and David Fincher (“Seven”). By the 1990s, he was scoring three or four films a year.

Journey to Middle Earth

In 2000, he took on his most ambitious project yet with Peter Jackson’s “Lord of the Rings” trilogy. Over the course of nearly four years, Shore composed a dense, 11-hour opus brimming with elaborate, interlocking character themes for the London Philharmonic Orchestra and choirs singing the languages of author J.R.R. Tolkien.

“What Howard does as well as any living composer is to understand the emotional content of movies,” said Viggo Mortensen, who played Aragorn in the trilogy. “He is capable of . . . showing a particular understanding of the subliminal power that music can provide [and] seems to thoroughly understand the essential rhythms of stories.”

“Lord of the Rings” earned Shore his three Oscars and has remained an outsize part of his life in the hundreds of live performances of the scores around the world. (He returned to Middle Earth with Jackson for the three “Hobbit” films.)

It also marked a turn in his life.

“Once the trilogy was finished, my pencil rested,” said Shore, who promptly began looking beyond the movie theater to the concert hall — “just for the finer brushstroke.”

“I had done a lot in film. I did a lot of the things that I had set out to do when I was younger,” he said, “where the concert pieces seemed like I could stretch out a bit. I could write in a more complex counterpoint if I wanted. It allowed a freedom to express ideas in music.”

He spent three years adapting “The Fly” into an avant-garde opera, which premiered in 2008. (The New York Times deemed it “ponderous and enervating . . . and the problem is Mr. Shore’s music.”) Since then, he has written a song cycle (“A Palace Upon the Ruins”) with text by his wife, Elizabeth Cotnoir, a piano concerto for Lang Lang (“Ruin and Memory”) and a cello concerto for Sophie Shao (“Mythic Gardens”).

The latter two will make their recording debut Feb. 17 on Sony Classical.

“There’s still a real interest and a love of film,” Shore said, “but I’ve got a bit of catching up to do.”

Last year, he provided a piano-driven score for Tom McCarthy’s Oscar-winning “Spotlight.” McCarthy was impressed with the veteran composer’s collaborative nature.

“He sort of leads with his mind, but he has a tremendous amount of heart,” McCarthy said. “You can feel that in his music, and you can feel it in his process. He’s a guy who doesn’t just start scoring — he starts talking a lot about themes and understanding the material and the journey of the story before he starts to write a note.”

The source of Shore’s deferential personality is easy to pinpoint.

“I think his Canadianness is very much a part of what makes him able to do that shape-shifting,” Cronenberg said. “It’s really part of the Canadian tradition — politically, even — to not impose yourself in an aggressive way but to be willing and able to compromise and to understand, therefore, other people’s point of view.”

“The seriousness of approach, I think, and the modesty of it is very Canadian,” Michaels agreed. “Not fighting for credit as much as fighting for it to be good.”

You may also like

Follow on:

facebook

Upcoming Concerts:

The Two Towers

Live to Projection

Ottawa, Canada

Jan 17, 2026

Royal Albert Hall

London, UK

May 1 - 10, 2026

Pittsburgh, PA

Jun 26 - 28, 2026

The Return of the King

Live to Projection

Seoul, South Korea

Jan 17 - 18, 2026

Munich, Germany

March 14 - 15, 2026

San Francisco, CA

April 30 - May 2, 2026

Royal Albert Hall

London, UK

May 3 - 10, 2026